Since returning from the archives in London, I’ve been working through a small set of correspondence that we have from the secretary of the Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb covering the years 1854 to 1856. These are crucial years for the association which was restructured in 1854 and which employed Samuel Smith as its chaplain in 1855.

As an historian, I am particularly fond of correspondence. It is about as close as you can get to the original characters of history without going back in time to shake their hand. After all, the letters that we now read were handwritten by people in the 1850s, sent by them across the country on mail coaches, and opened and read by others. I like to think that if we had very sensitive instruments, we might pick up traces of the hands that held them and the eyes that read them.

… That said, given some of the handwriting of those involved, I do breathe a sigh of relief when typewriters begin to be used in the early 20th century.

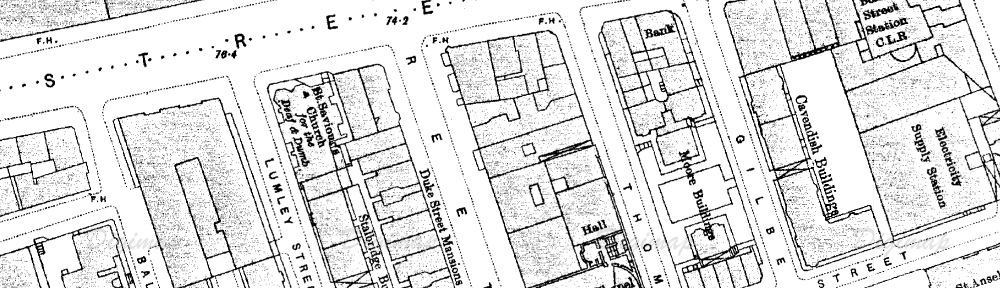

Many of the letters come from schools for deaf children. Some of these used standard letter-headed paper. Here are two examples from the Edgbaston and Northern Counties schools.

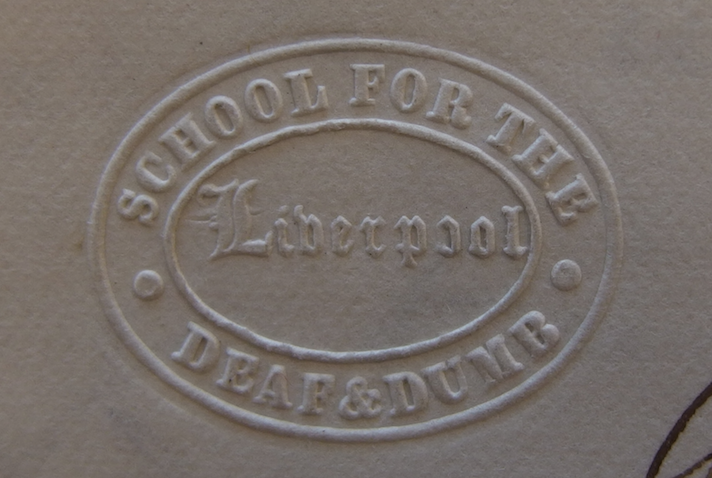

My favourites, however, come from the Doncaster and Liverpool schools, which did not use a printed letterhead in their correspondence with the Association, but instead embossed their name on to any piece of paper used using a hand press. The result is a wonderfully tactile gift from the mid-19th century, created by the hands of those whose stories we are telling, which has lasted as something that we can still touch today.

They’re beautiful . . . and thanks for posting them! I wish I could feel the sculptural lines, but the sight alone is a feast.

It is… it was great to have a good camera, to be able to take really good close-up pictures. They look almost 3D! Thanks for reading Linda 🙂