With engagement activities in Bristol, preparations for a workshop, archive visits, bank holidays and some leave time, May has been extremely busy.

But, back from the archive, and with well over 10,000 photos of data now, we’re in a position to take stock and start to share some of what we’ve found.

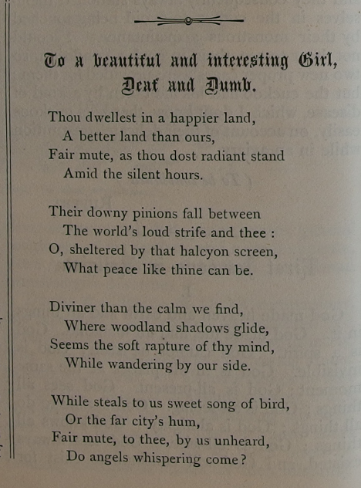

A lot of what we’ve got is text, and we’ll have to extract information from there as it’s useful. But some things we can bring you straight from the archive. Like this, from the 1873 edition of the ‘Magazine intended chiefly for the Deaf and Dumb’, a poem entitled “To a beautiful and interesting Girl, Deaf and Dumb”.

The poem reads:

To a beautiful and interesting girl, Deaf and Dumb

Thou dwellest in a happier land,

A better land than ours.

Fair mute, as thou doest radiant stand

Amid the silent hours.Their downy pinions fall between

The world’s loud strife and thee:

O, sheltered by that halcyon screen,

What peace like thine can be.Diviner than the calm we find,

Where woodland shadows glide,

Seems the soft rapture of thy mind,

While wandering by our side.While steals to us sweet song of bird,

Or the far city’s hum,

Fair mute, to thee, by us unheard,

Do angels whispering come?

(Jan 1873, p.15.)

We don’t know who wrote the poem, but they were clearly hearing… and (for me at least) there’s some suggestion that they were rather taken with the girl in question.

What really strikes me, though, about this poem is the way that the ‘nature’ of the girl is imagined. Her reality is ‘happier’, ‘better’, ‘radiant’, ‘sheltered’, ‘Divine’ even… separated from the hearing world by a ‘halcyon screen’ of silence that may be so blessed that it even allows her to hear angels.

‘Hear’ angels? Who can presumably whisper past the limits of language, or perception, directly into her mind.

Perhaps this is an accurate reflection of what the author understood Deaf people’s reality to be in 1873. Perhaps it is actually a way of rendering Deaf realities somewhat ‘other worldly’, or exotic and so making them an object of difference. Perhaps it’s simply a whimsical expression of affection.

But it’s certainly quite different from the language of ‘affliction’ that often appears in descriptions of Deaf people from the same period.