The first magazine about (or for) Deaf people to really gain national traction in the UK was the ‘Magazine intended chiefly for the deaf and dumb’. Edited by Samuel Smith, it ran from 1873 until 1878.

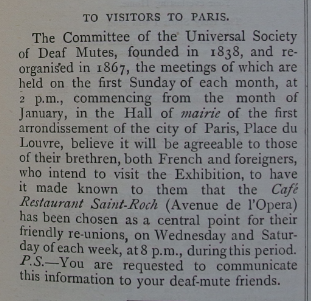

In the edition for August of 1878, there is a small notice that–perhaps because my previous research focused on the French Deaf community–jumped out at me:

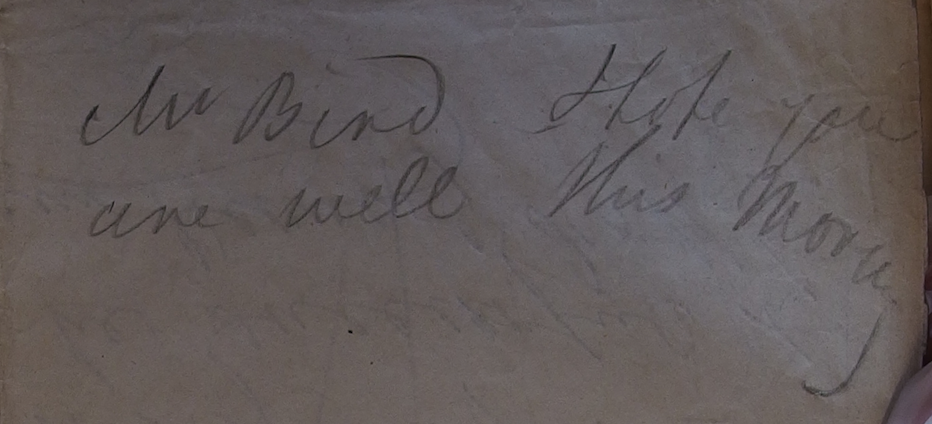

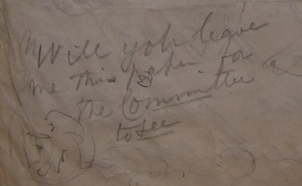

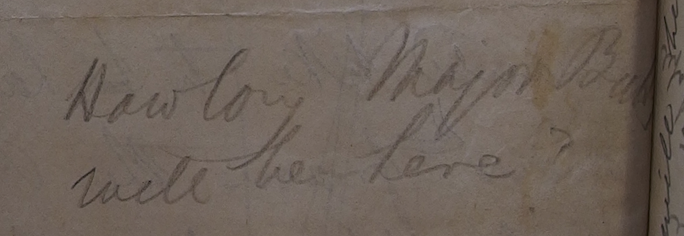

It reads:

TO VISITORS TO PARIS. The Committee of the Universal Society of Deaf mutes, founded in 1838, and reorganised in 1867, the meetings of which are held on the first Sunday of each month, at 2 p.m., commencing from the month of January, in the Hall of mairie of the first arrondissement of the city of Paris, Place du Louvre, believe it will be agreeable to those of their brethren, both French and foreigners, who intend to visit the Exhibition, to have it made known to them that the Café Restaurant Saint-Roch (Avenue de l’Opera) has been chosen as a central point for their friendly re-unions, on Wednesday and Saturday of each week, at 8 p.m., during this period. P.S.-You are requested to communicate this information to your deaf-mute friends.

The notice is wordy and the language shows traces of having been written by a French speaker… but what’s most interesting is the way that the dates and intent flow around each other to give a tiny glimpse of both a Parisian Deaf space and its connections into an international Deaf network.

Setting the scene a bit, the Parisian Deaf community were not in great shape in 1878. In fact, they were in a bit of a mess. Lots of internal divisions and rivalries meant that the community was far from united…

In the hearing world, however, things in deaf education were steaming ahead. 1878 saw the first International Congress on the Education of Deaf people… the precursor to the notorious Milan congress of 1880. The congress ran at the end of September and was organised to coincide with the World Fair. It was organised by the Pereire Society – a society established by two prominent brothers who were famous French industrialists (extremely wealthy) to celebrate the work of Jacob Pereire, the first oral teacher of the deaf in France.

Comparing the two worlds… you have a Deaf community in disarray, whose very existence is being energetically attacked by a large, powerful, rich hearing-led movement of modern educational ‘progress’.

And yet, the Deaf community in Paris still had time to think about and open up Deaf spaces.

The intent is clear – and the choice of the Café is also interesting… The St Roch church (which is just down from the Opéra) was the resting place of the remains of the Abbé de l’Epée who was, of course, famous within the French Deaf community for his support of sign language.

So, what we have here is an advert that says “Despite our differences, and despite the events going on around us, there is something that unites us… and even unites us internationally. If you are travelling to Paris – particularly if you are coming over for the congress on deaf education, don’t be a stranger. We want to celebrate the centrality of our language and our community… Deaf space will be there to welcome you. Come and find us”.