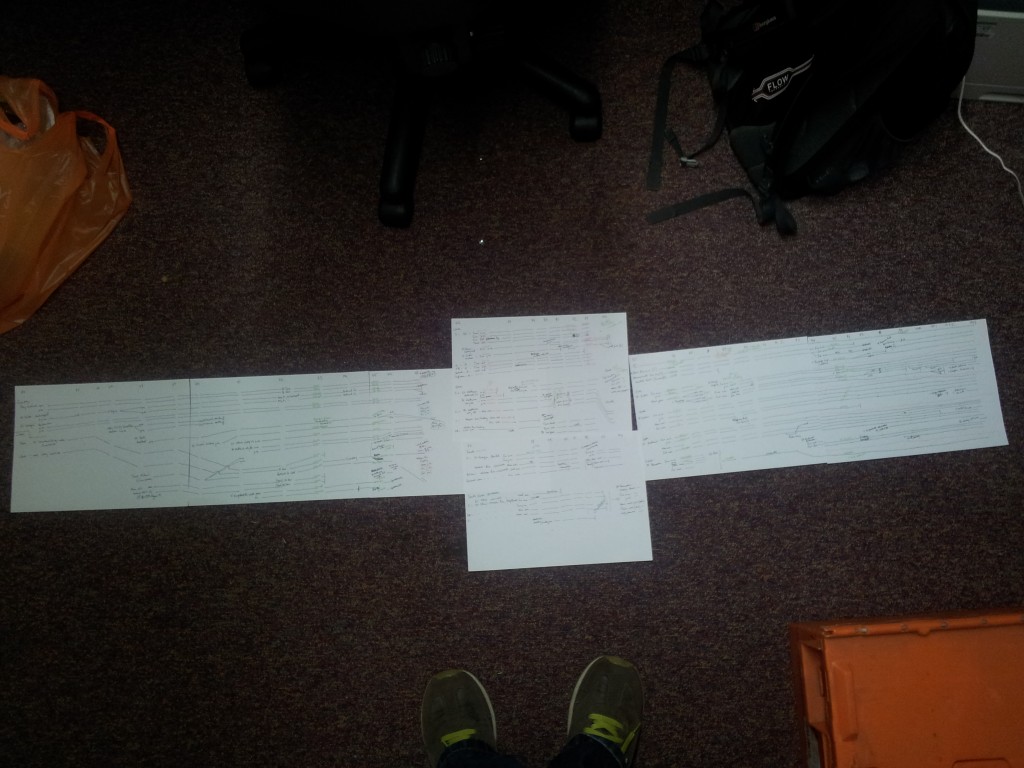

Today, I thought I’d share something of what I’ve been doing. Since this morning, I’ve been working through the descriptions of activities in the Annual Reports of the AADD from about 1864, noting down all the religious services, lectures, classes and other meetings that they had, where they had them, and who was in charge of them. I’ve been drawing lines to map where they continued from year to year, where they started, and when they stopped.

This is the start of a big piece of work to scope out the whole spectrum of the AADD’s work, and to look at things like

- Periods of growth, and shrinking

- Handovers from one missioner to the next

- Development of particular areas in London

- Types of services and when they started

- … and so on.

So far, all I’ve really been able to do is map the activities generally, with a few comments on who was involved, and some of the very basic changes in the organisation.

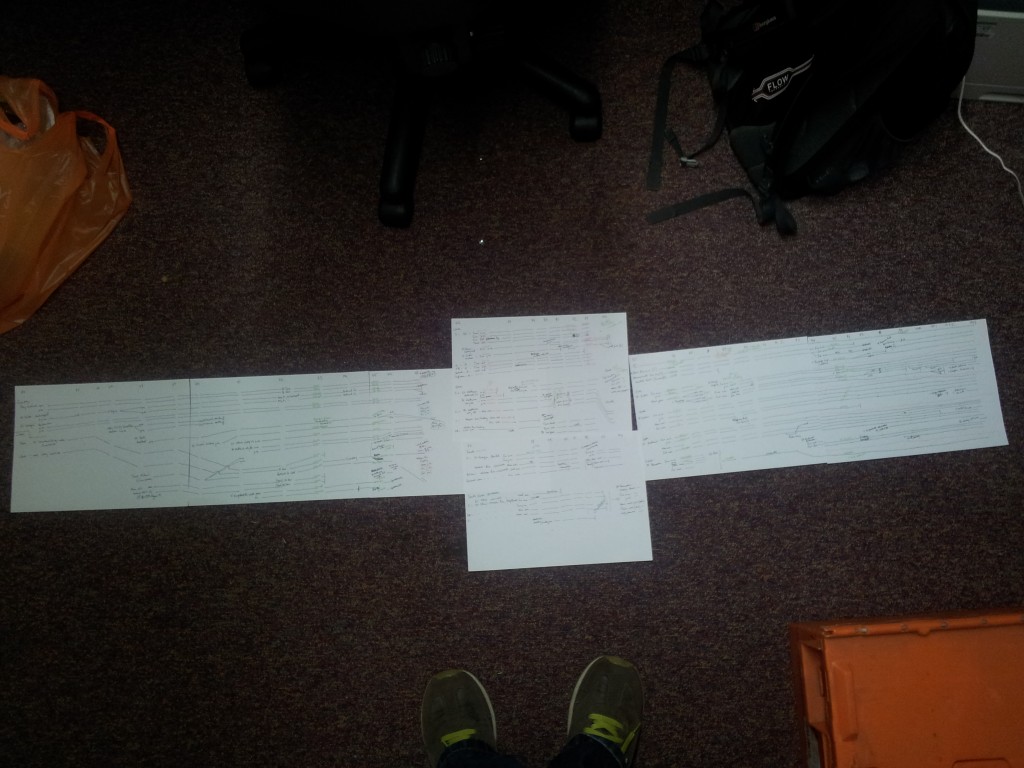

So here’s the whole map (excuse my feet):

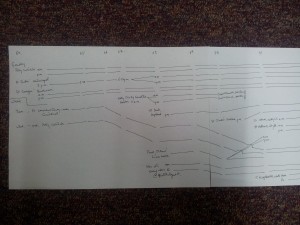

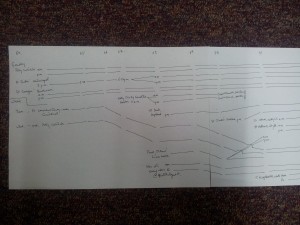

Here’s the first page,

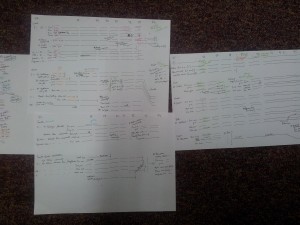

and the last…

You can see the growth in activities… and that’s without taking into account that the top and bottom lines in the final picture represent entire churches… so they had about 10 or so services within that one line.

The wider section in the middle is when the AADD split its activities into four (and then five) districts, each with its own staff.

This map will need finishing, and formalising, and then other information can be added. The number of those attending services, who ran which service (there’s a little of that already if you look closely), what the missioners daily timetable and weekly activities looked like, and so on.

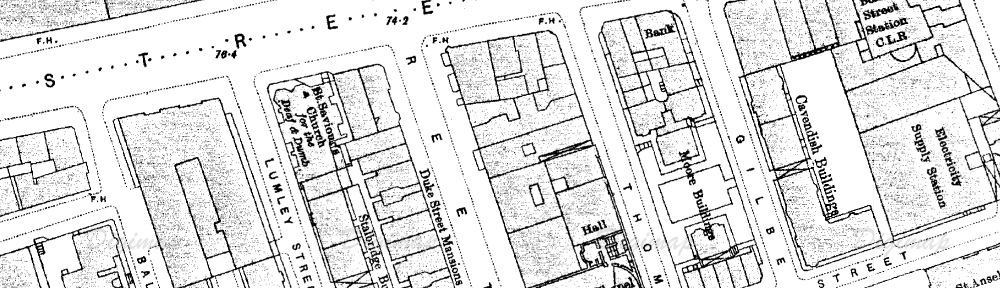

We’ll also be able to start locating all of the buildings that were used, and see how their location corresponded to Deaf populations, transport, and other historical information about London at the time.

Gradually, we can build up a picture of the Association, and how it responded to needs within the Deaf community and, as it became more of an established charity, how it responded to the economic environment.

I’ll put more up as we get there… only about another 25 more years to map!!

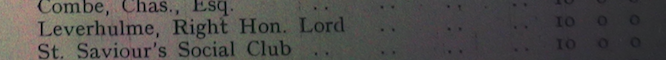

Lever gave a direct donation of £10 – which at the time was about £500 – to the work of the AADD.

Lever gave a direct donation of £10 – which at the time was about £500 – to the work of the AADD.