One of the greatest pleasures that I have, as an historian, is stumbling upon a piece of evidence that confirms something that we already know from somewhere else.

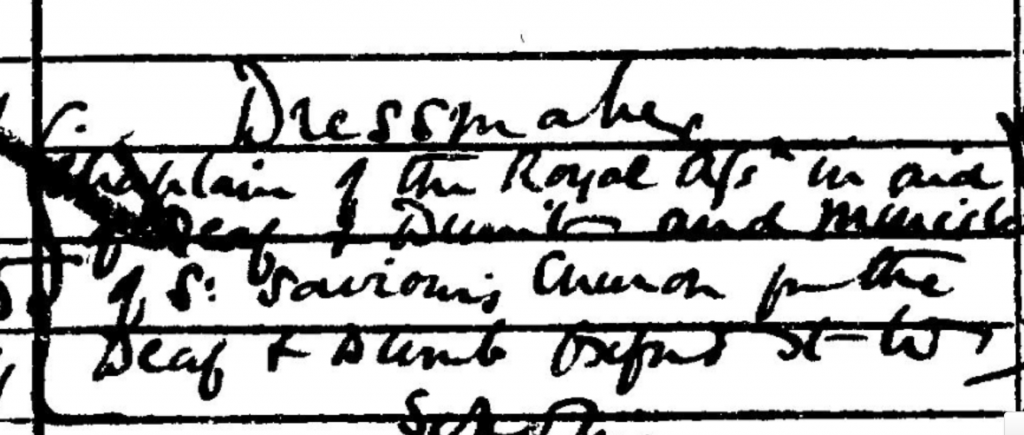

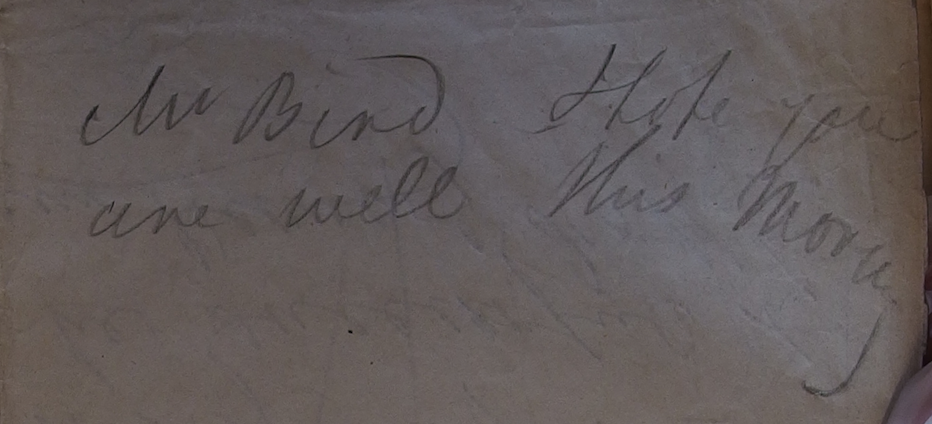

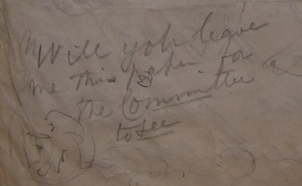

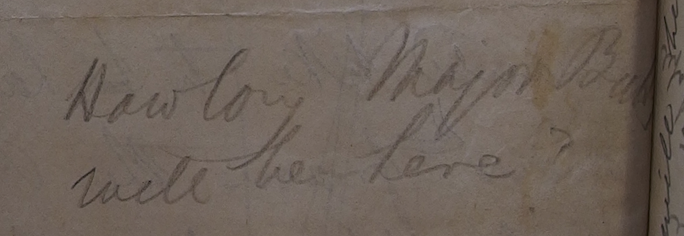

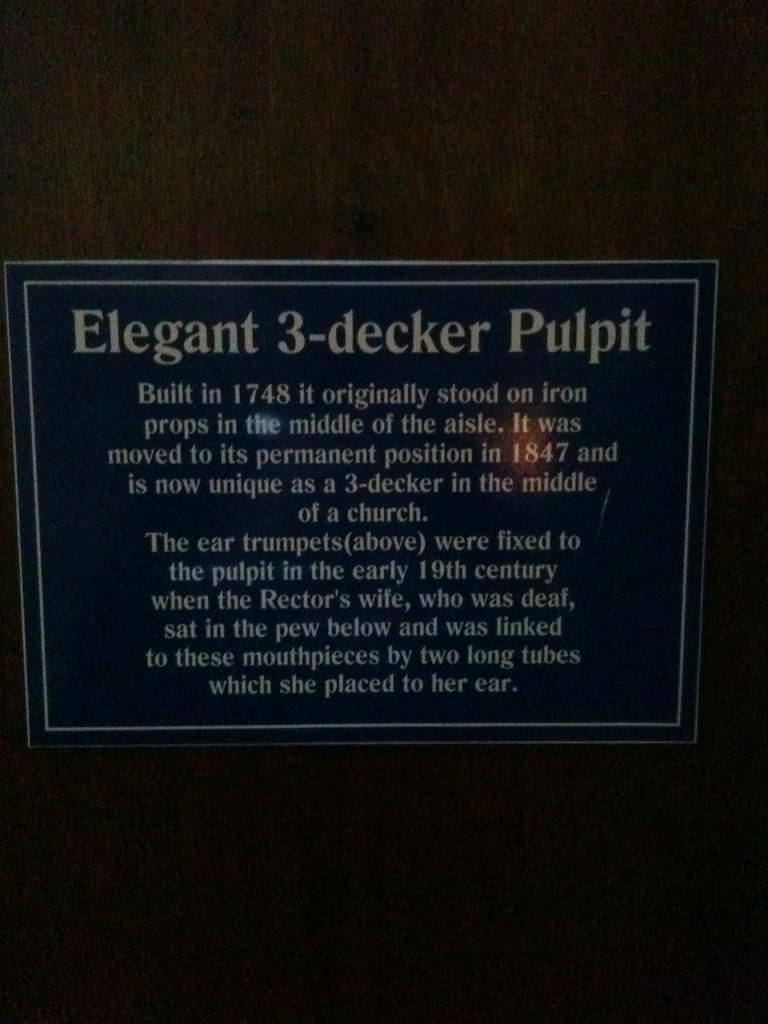

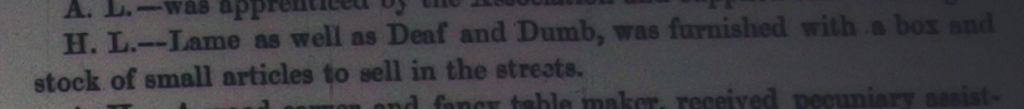

This morning, for example, I stumbled upon this – in a biography of Charles Baker, who was the headmaster of the Doncaster school for deaf children in the 1850s.

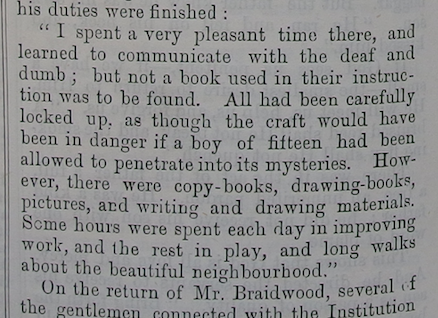

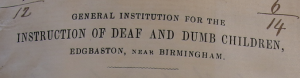

This is a cutting from an 1875 biography of Baker, and it describes a visit that he made to the school in Birmingham run by the grandson of Thomas Braidwood, the famous educator of deaf children.

The Braidwood family were renowned for being extremely secretive about their methods, so much so that when Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet visited London in 1815, the headmaster of the London school (owned by Braidwood, and run by his nephew Joseph Watson) refused to tell him what his method was unless Gallaudet agreed to stay and work for him.

Gallaudet refused, and travelled to Paris instead, where he persuaded Laurent Clerc to leave the Parisian deaf school, and travel to North America. Between Clerc and Gallaudet, they started the American deaf school at Hartford, and the rest… as they say… is history.

Braidwood’s methodological secrecy in London had a direct impact upon the direction that Deaf education in America took. Had he been less secretive, American Deaf education might have turned out quite differently. And here, Baker’s biography gives us confirmation of that secrecy.

It is a real pleasure to find evidence like this that has a direct link to other stories that we already know. It’s like the two stories are just one, that connect… and something amazing happens.

As a historian, it is a bit like watching the scene from Lady and the Tramp (watch from 1 min 15 secs) where Lady and the Tramp pull out the same strand of spaghetti from different ends, and end up kissing.

(I guess you have to really love history to see it like that… but I do!)