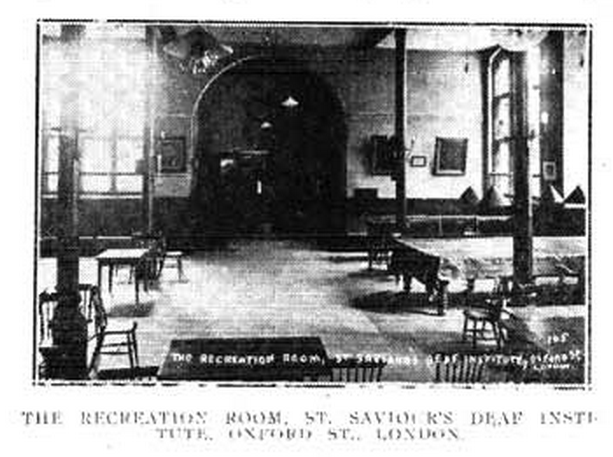

The last few days have been quite interesting – for a few weeks, I’ve been talking to Emma Tracey from the BBC about an article on St Saviour’s. The history of the church is interesting, but what was more interesting to her was the fact that the RAD (who own the Acton St Saviour’s) are selling (or have sold) the church.

The article came out on Sunday and was entitled:

“UK’s first purpose-built deaf church to close”.

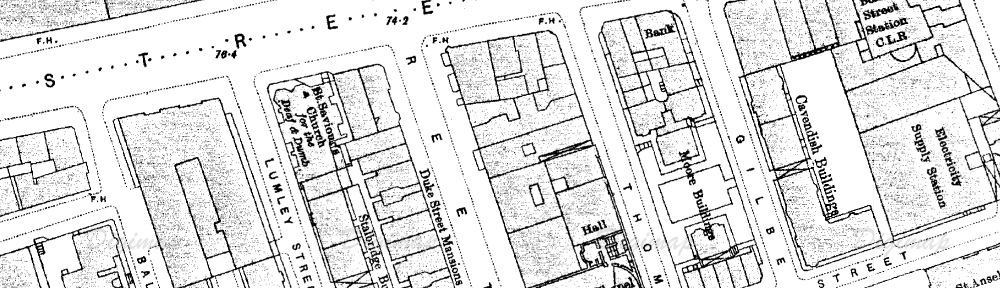

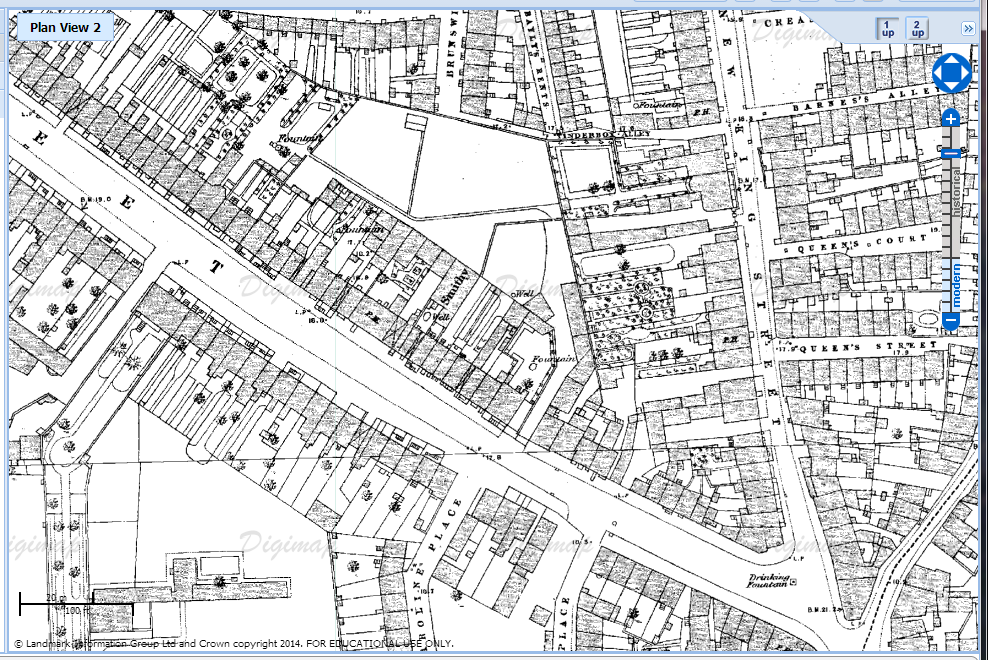

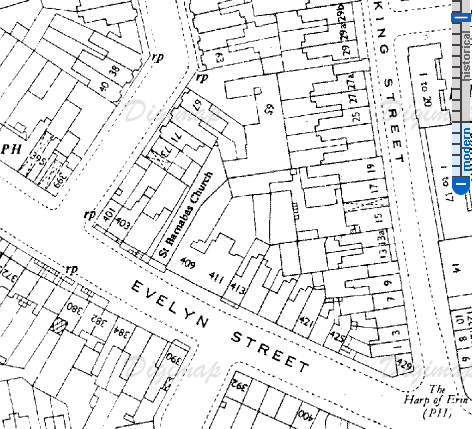

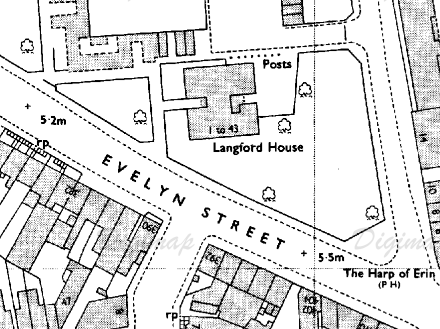

Acton is actually the ‘last’ purpose-built Deaf church – as in, it’s the last building remaining that was built specifically for Deaf people. The Oxford Street St Saviour’s was the ‘first’… Still, it’s all been the same congregation, and what’s important is that people are reading about the church, and the project and learning something.

And that’s great – although it has highlighted an interesting issue, over what our role is… or should be with regards to ‘policing’ the sale.

You see, we are researchers. As such, our job is to research; to gather information, deal with it neutrally, interpret it carefully, report it sensitively. We’re here to tell a story.

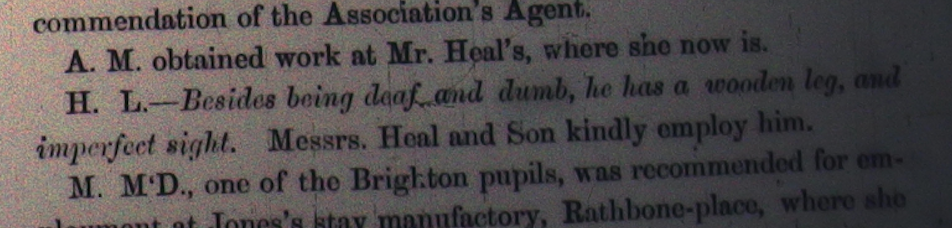

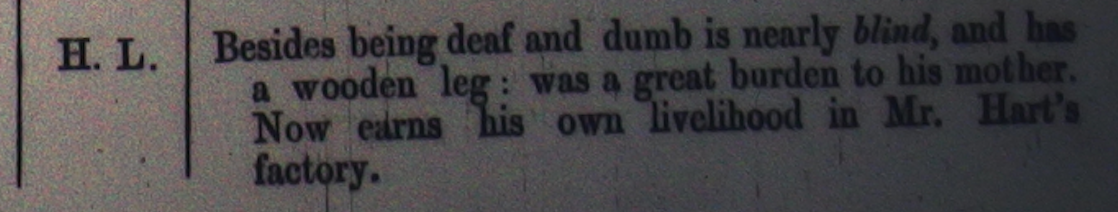

But… through researching the Acton church, we (the project team) have found out things that are hard to stomach… we’ve found out, for example, that some of the artefacts from the original St Saviour’s have been sold on and lost. Not on purpose… but because someone read the dates on them wrongly and thought they weren’t important.

This isn’t anyone’s ‘fault’ per se… it was a mistake, but for those who really care about the church and its story, the carelessness hurts more than the original intention to sell!

What should our role be? Should we ignore the mistakes? Should we step in and try to influence things?

Should we even, as we’ve been asked… attempt to stop the sale?

Doing too much would be an abuse of privilege… it would certainly put us on shaky ethical grounds to interfere in the internal affairs of organisations that we’re working with and that have, so far, been very honest and open with us.

Doing too little though is surely negligence, and an abdication of responsibility.

Our solution so far has been to pass information about this to the local Deaf community, and leave it to them to raise it with the organisations concerned. But that puts a lot of pressure on Deaf people who can’t scurry around after every issue we notice.

… all of this got us to wondering why, when history is so important for the Deaf community, it is so easy for powerful organisations to simply ignore the impact of their decisions, and do what they want?

- Is it that Deaf people don’t care? Or that some don’t care, and so there’s no united vision?

- Or is it that Deaf people do care, but are tired, under-resourced, and needing support?

- Or is it that Deaf people are resisting, but are being swept aside and ignored?

- Or something else?

We may not be able to directly intervene with the organisations themselves. But we can support the Deaf community with ideas, skills-training, vision, resources… and we can tell the story of how Deaf people are being ignored.

It would seem that, in a situation like this, that is our role.