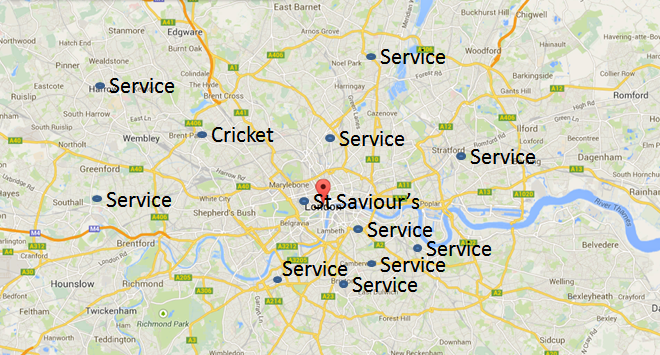

The Scripture, Dissent, Deaf space project is gradually gathering pace. So far, we’ve spent the month settling into a new office, going through PhD applications, booking archive visits, wrestling with the admin systems of the university (a lot), and working out some initial ways into the data.

We’ve started to pull out lists of who was involved, and when, and where, and what they did. Trying to make sense of it all has generated lists of more things that we need to know. The lists just get longer and longer.

This is a normal part of the process though, so it’s not something to be too worried about at the moment… but at some point, we will need to start defining the edges of the project. We don’t have time or funding (unfortunately) to follow up on a lot of the leads. Those will have to be new projects, and proposals.

I’ve spent more than one afternoon reading previous research to try and locate the period in a bigger picture of Deaf and church history, and national history more generally.

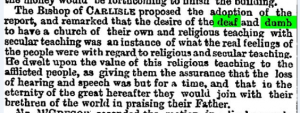

One of the things that we can do to help with that, because the university pays for the library access, is get to historical newspaper records from the time of St Saviour’s to start having a look at what people were writing, and saying about Deaf people and about the church itself.

This is all public domain, and well out of copyright, so we can share some of it with you without fear of breaking any rules.

I’m particularly interested to use the way that people describe Deaf people’s situation, to see how they understood and described the reality of the Deaf community at the time

One of the questions I’ve always had in the back of my mind for this project is “What did people think was going to happen to Deaf people when they got to heaven? Would they sign, would they speak? Would everyone else sign, or speak?”

Well, this is only one clip, but it provides some kind of answer for the moment;

(from the Times, 15th May, 1872)

… He dwelt upon the value of this religious teaching to the afflicted people, as giving them the assurance that the loss of hearing and speech was but for a time, and that in the eternity of the great hereafter they would join with their brethren of the world in praising their Father.

The Bishop of Carlisle comes across as rather a pompous person who knew little of Deaf people. But the suggestion is clear. He believed that Deaf people would be able to hear and speak in heaven, and that this would somehow reconcile them with the rest of humanity around worship.